Posted by Stephen hEAD on 16th Oct 2025

Koa Wood: History, Rarity, and Why It Makes Incredible Instruments

Koa Wood: History, Rarity, and Why It Makes Incredible Instruments

Koa is one of the most remarkable woods in the world. It’s also one of the most limited. It only grows in Hawaii, and every piece of it carries the story of the islands — their environment, their history, and their people.

The first time I worked with koa, what struck me most wasn’t just how it looked. It was how it felt. There’s something different about the density, the way it cuts, and how it reacts to light. Also, it really does sound amazing. Just the sound of tapping a koa board, it is so musical. It’s easy to see why Hawaiian builders have always held it in such high regard.

WHERE KOA COMES FROM

Koa (Acacia koa) grows on the slopes of Hawaii’s volcanic mountains — places like Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. It typically grows between 2,000 and 6,000 feet above sea level, in mineral-rich volcanic soil and heavy, moist air. Those conditions are impossible to reproduce anywhere else, which is why koa exists only in Hawaii.

The tree itself is unique. As it matures, it changes leaf structure to collect moisture directly from clouds and fog — an ability called “fog drip.” Koa also produces its own nitrogen, which helps feed the surrounding forest. The result is a tree that’s deeply tied to the island ecosystem and supports a wide range of native species.

That same environment — wind, sun, and constant weather changes — is what gives koa its figuring, color, and strength. Every piece reflects the environment it grew in. If you’re interested in how different woods shape tone, I explain it more in How Tonewoods Affect Sound

HISTORY AND MEANING

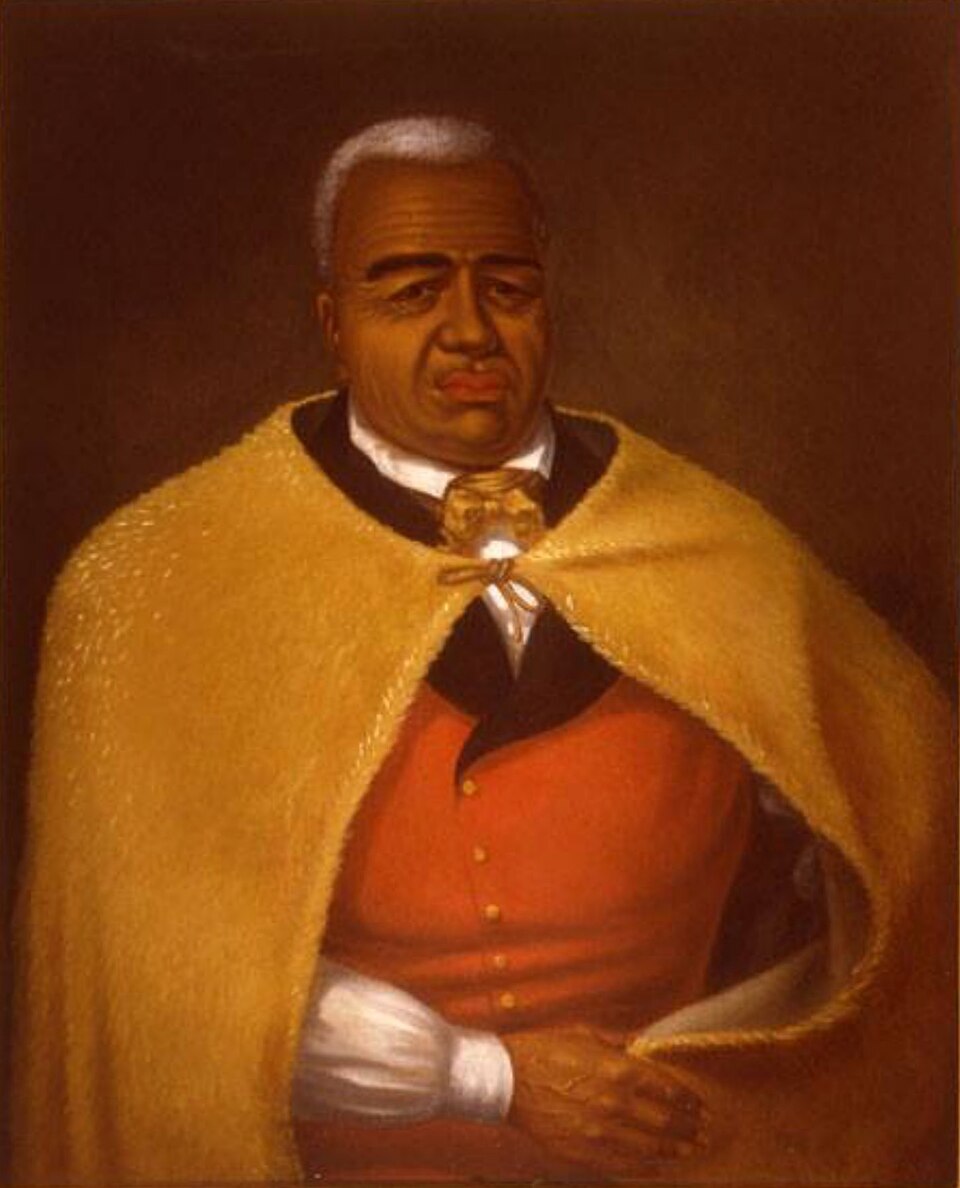

In Hawaiian culture, koa means “warrior.” The wood was used to make canoes, paddles, surfboards, and weapons. During the time of King Kamehameha, koa became “kapu” — reserved for Hawaiian royalty. It was seen as a symbol of courage and leadership, not just a building material.

That sense of respect still feels relevant today. I wrote about this idea in Tradition Isn’t the Goal — It’s the Byproduct of What Works. Working with koa carries a kind of responsibility. You’re handling something that was once sacred, and I try to approach it that way in the shop.

WHY KOA IS RARE

Koa’s rarity has real reasons behind it. It’s not hype.

The first is geography. It grows only in Hawaii, and there’s a limited amount of land where the conditions are right.

The second is history. In the 1800s, most of Hawaii’s old-growth koa forests were cleared for cattle ranching. The largest and oldest trees — the ones with the deepest curl and most stable grain — were lost.

The third is time. Koa takes 50 to 80 years to mature enough to develop the color, density, and curl that make it valuable. Younger trees tend to be straight-grained and lighter in tone.

The fourth factor is regulation and stewardship. Harvesting koa from public land is illegal, and most of the usable wood now comes from fallen trees or managed private forests. The supply is small and carefully controlled, which is exactly how it should be.

Add global demand to the mix — especially from the guitar industry — and you end up with a tonewood that’s genuinely scarce.

WHY IT MAKES GREAT INSTRUMENTS

Koa’s beauty gets a lot of attention, but what matters to me most is how it performs. As a solid tonewood, koa sits in a balanced place between mahogany and maple. It’s dense enough to stay articulate, but not so hard that it loses warmth.

Tonally, koa has a focused midrange, smooth highs, and a rounded low end. It’s musical and well-behaved. When new, it can sound bright and tight, but it opens up with use. The more it vibrates, the more it seems to relax. That makes it an ideal wood for instruments that are meant to age with the player.

Using solid koa in a Cajon, I notice the clarity first. The bass is controlled, not boomy. The highs are crisp but not sharp. The midrange has a kind of warmth that makes it easy to blend with other instruments. It has a overall tone that feels complete.

BUILDING WITH KOA

Koa machines and sands well if you stay sharp and patient. The grain can interlock, which means you have to pay attention to direction to avoid tear-out. It’s not a wood that tolerates being rushed. It takes finish beautifully. When done right, the surface glows and the grain has incredible depth.

That same depth you see in the grain is also part of the sound. The curl and figure create micro variations in density that scatter vibration in a musical way. It’s one of those rare cases where beauty and performance come from the same structure.

WHY IT MATTERS

When working with koa, I think about how long it took for it to get here. A tree that’s been standing for half a century or more finally becoming an instrument that might last another lifetime. There’s something grounding about that.

Koa is rare. It’s beautiful. And it’s musical. For me, it is very special. It’s not just about the look or the price or the scarcity. It’s about what it represents —patience, endurance, and connection between nature and sound.

When a piece of koa becomes a drum, it continues the same cycle it’s always been in: shaped by time, by touch, and by vibration. That’s something worth respecting. That same respect for the process — and for other craftsmen who share it — is what led to my collaboration with Manito Percussion. I wrote about that experience here: Building the Manito Cajon: A Journey of Wood and Respect Between Builders

More tonewood studies and behind-the-scenes builds: Kopf Percussion Blog