Posted by Stephen C. Head on 11th Jan 2026

Why Maker’s Marks Matter in Handcrafted Instruments

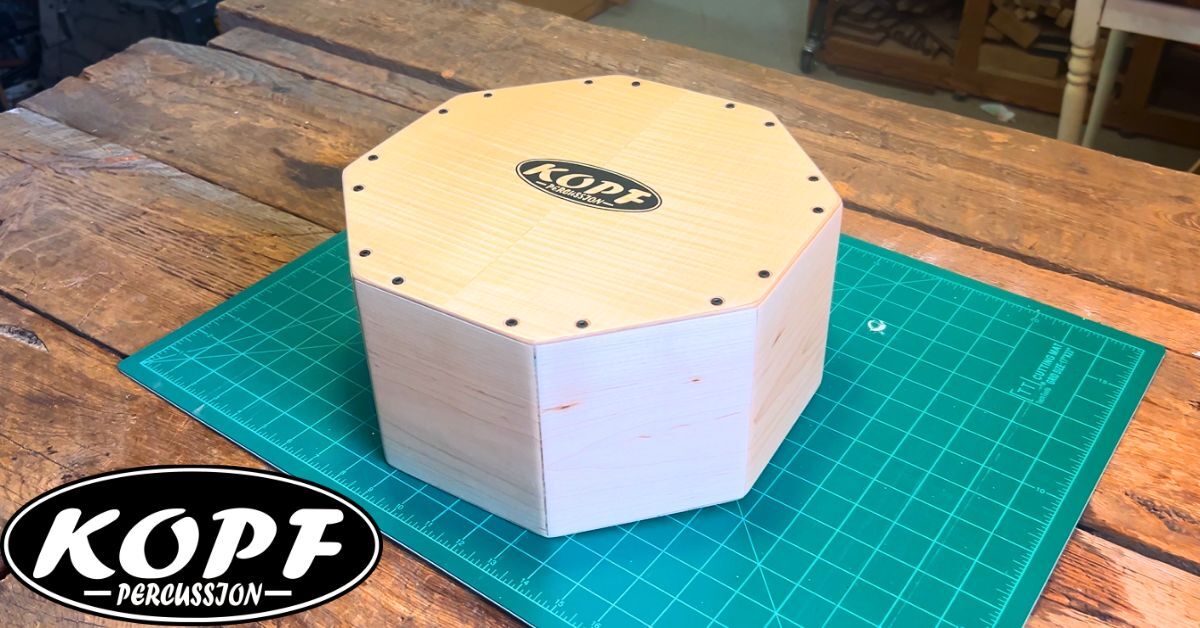

A cajon is a simple instrument by design. At its core, it is a box with a playing surface, internal voicing, and a relationship between wood, tension, and touch. There are limits to what can be patented or protected in a meaningful way. That simplicity is part of what makes the instrument honest. It is also what makes authorship harder to see once the instrument leaves the shop.

After seventeen years of building cajons full time, I have learned that simplicity does not reduce the importance of origin. It increases it. When every instrument is different, especially fully custom work, the question becomes practical rather than philosophical. How does anyone know where it came from?

Long before modern branding existed, craftspeople marked their work. Blacksmiths stamped blades. Furniture makers branded rails. Luthiers signed soundboards or placed labels inside instruments. These marks were not decorative. They were statements of responsibility. A maker’s mark said this came from my hands, and I stand behind it.

Those traditions existed long before formal trademark law. As trade expanded and goods moved farther from their makers, marks became even more important. Over time, trademark systems developed to formalize something craftspeople had already been doing for centuries. A mark identifies the source of an object. It distinguishes one maker from another. It allows reputation to follow the work.

That is what a trademark does in practical terms. It ties an object to its origin in a way that can be recognized and protected. In fields where designs are complex and patented, that connection can live in form alone. In fields like handcrafted percussion, where designs are simple and ideas move quickly, that connection has to be visible.

I have seen this firsthand. Over the years, I have made decisions based on comfort, durability, and feel. One example is leveling the corners of a cajon so it is easier on the hands and legs over long sessions. When I started doing that, it was uncommon. It worked. Over time, it became widespread. That is not a complaint. That is how good ideas move through craft. But it is a clear reminder that most elements of an instrument can be copied once they prove useful.

Quality can be replicated. Materials can be sourced. Construction details can be studied and adopted. In a simple instrument space, almost everything about a drum can eventually be imitated. The one thing that cannot be legally or ethically copied is a maker’s mark. That is why it matters.

There is also a practical business reality that cannot be ignored. I learned early on that paid advertising is not a game I can win. I am a one man shop. I will never have a marketing budget large enough to compete with corporate advertising. In the cajon market, there are large companies with deep pockets and constant visibility. Trying to outspend them is throwing money away. They will win that contest every time.

The advantage I do have is craftsmanship. Uniqueness. The ability to build an instrument around a specific player rather than a demographic. That kind of work does not scale through ads. It spreads through recognition. Through players seeing an instrument, hearing it, touching it, and knowing who made it.

In that context, the maker’s mark is not just tradition. It is communication. It is how the work carries its own story forward without advertising dollars behind it. When someone encounters one of my drums in a studio, on a stage, or in a photo, the logo is the only reliable way that connection is made. Without it, the work becomes anonymous, no matter how well it is built.

When I trademarked my logo, it was not a marketing exercise in the conventional sense. It was a practical decision rooted in experience. It was a way to protect attribution in a field where originality is often quiet and incremental rather than dramatic. The logo is the only element on the drum that is uniquely and permanently tied to me.

It is important to separate ownership from authorship. Once a drum leaves my shop, it belongs to the player. That is not in question. They will play it, travel with it, and live with it. But the fact that I made it does not disappear with the sale. The logo is not about control. It is about responsibility. It says I built this instrument and I am willing to put my name on it.

That is why the logo lives on a playing surface. Not to dominate the instrument and not to distract from the music, but to exist where the relationship between player and instrument actually happens. It is placed deliberately and with restraint, but it is not hidden. A maker’s mark that is tucked away stops doing its job.

Consistency is another part of this that often goes unnoticed. The reason people recognize my work is not because of one standout feature. It is because the decisions are consistent over time. The way instruments are built. The way they are finished. The way they are presented. Logo placement is part of that continuity. Changing it casually introduces inconsistency into a system that only works because it is repeatable.

There is also a long view to consider. A marked instrument carries provenance. Its origin is clear. An unmarked instrument relies on explanation and memory. In resale, in studios, on stages, and in photographs, clarity adds value. Ambiguity does not.

None of this is about ego. It is about honoring craft, lineage, and responsibility. A maker’s mark is not a signature added for attention. It is a quiet statement that the work has a source and that the source stands behind it.

In a simple instrument, where almost everything can be copied once it proves itself, that matters more than ever.